“Leeches are a really interesting - and simple - model organism,” Whitaker says. In recent years, scientists have studied everything from leeches’ genetic makeup to their neurological structures and gut bacteria. “ have a suite of chemicals that they release in their saliva when they bite,” including anticoagulants and painkillers, he notes. Part of why leeches have been involved in medicine for so long is the unique cocktail of medically useful compounds they release while feeding, says Joerg Graf, a molecular biologist at the University of Connecticut in Storrs. Their jaws consist of three layers of blades, making the distinctive Y-shaped incision they make in the flesh of their prey essentially painless. There are more than 700 species of leeches, all carnivorous, ranging in length from a few hundredths of an inch to greater than 18 inches. “They’re interesting, they’re different and they’re ancient,” says Iain Whitaker, a professor of plastic and reconstructive surgery at Swansea University in Wales. But many of those supposed treatments ended up doing more damage than good, and by the late 19th century bloodletting was widely discredited.īiomedical researchers never completely lost their fascination with leeches, however.

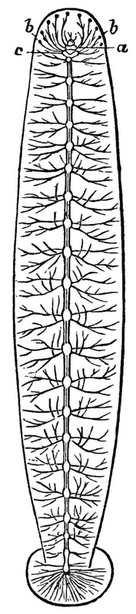

LEECH BRAINS SKIN

Ancient Indians, Mesopotamians, Egyptians and Greeks used them for bloodletting, which was supposed to treat ailments ranging from skin conditions to cancer. Healers have been using leeches for thousands of years.

“People are definitely becoming more aware of it.” Leech research “is on the rise,” says Paul Cherniack, a professor of geriatric medicine at the University of Miami who wrote a paper on the use of leeches. But questions of safety and effectiveness remain for the uses that go beyond what the FDA has approved, and using leeches for more treatments may mean trouble for the leeches themselves, since many species are already threatened. Now, almost ten years after the FDA approval, scientists are exploring some additional clinical uses for leeches, primarily for conditions that limit blood flow, like arthritis. Leech saliva also contains hirudin, an anticoagulant that helps the blood keep flowing even after the leech fills up. Leeches “can help the finger to bleed and get off the excess of blood that the venous system can’t quite handle,” Levine explains. Blood flow can become congested and eventually stop altogether, causing the digit to die. With small, tenuous veins and more robust arteries, newly reattached fingers can easily fail due to poor circulation. Their primary use is in reconstructive surgery and microsurgery to help return blood flow to severed veins. The Food and Drug Administration approved them as “medical devices” in 2004. More than a century after most physicians stopped using them in their everyday practices, leeches are back. She became so invested in her treatment, Levine recalls, that she even named her leeches - choosing standard male names, like Michael and Bob. “After about a week or so of treatment, she was able to leave with an intact finger, without surgery,” Levine says. After a few more cycles with fresh leeches, the bartender’s finger had turned from purple to a healthy pink. The leech swelled up as it siphoned off the pooling blood until, after a few hours, it fell off, engorged and satiated. He then carefully placed the leech next to the puncture, and it promptly clamped on and started sucking. Using a needle, he pricked the end of the bartender’s injured finger to get the blood flowing. Levine didn’t reach for a scalpel or forceps instead, he used leeches. So Levine knew exactly which tools to use when a young female bartender came in with a “ring degloving” - she got her ring caught on a hook, which pulled off a large area of skin on her finger, like taking off a glove. “Basically, we put back that are cut off” – fingers, toes, noses, ears and even testicles, he says. Jamie Levine, the chief of plastic surgery at Bellevue Hospital in New York City, is a hit at dinner parties he always has a good story from the office.

A rich life among the dead Nick Stockton

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)